Startup Capital. Most entrepreneurs begin with money of their own, and/or money from friends and family. At this stage, people tend to invest because they know/trust/love you, so they are not going to be as tough on your business plan as others. They will also be “patient capital” — they’ll be happy to make a profit on their investment, but they probably won’t be too upset if it takes longer than you expect. These rounds are typically less than $100,000 in total. Be sure not to take money from anyone who can’t afford to lose what they put in, and always make it clear that many things can go wrong, and that they could lose their money. This startup capital is typically used to the company prepared to launch its business by designing a product, creating samples or prototypes, and/or conducting market research. Some companies can get all the way to profitability using startup capital. Others must move on to the next stage.

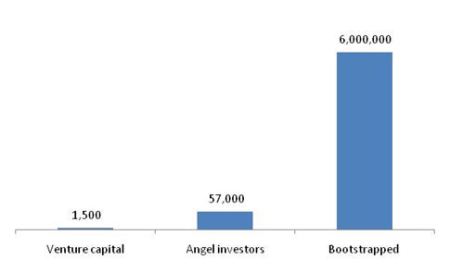

Seed Round. Many companies seek outside[1] capital in order to build their businesses. This stage is typically called a “seed stage,” and most entrepreneurs get seed stage capital from angel investors.[2] Angel investors are people who invest their own money on an amateur basis—as opposed to venture capital firms, which invest money in funds, on a professional basis. Each year, angels invest about $26 billion in more 57,000 companies,[3] more than 10 times the number of companies venture capital firms back each year.[4] Some angels invest alone, and others invest through groups.[5] Their levels of sophistication can vary widely; those in groups tend to be the most savvy, which makes them tougher to persuade but also more valuable. Most angel rounds are below $1 million. The investments can be used for many different purposes, but in many cases they are designed to get a company to the point where it has a product or service up and running, and enough paying customers to prove that their concept works ( “proof of concept”).

Series A Round. Companies that need significant amounts of capital after burning through their seed funding often seek funding from venture capital firms (“VCs”). For the average entrepreneur, VCs are tough nuts to crack. First, you’ve got to have the right background. Yes, VCs sometimes invest in unknown, first time entrepreneurs, but there’s usually a back-story. More often, they invest in teams led by seasoned entrepreneurs with track records of success. Next, you’ve got to have the right idea. VCs take a portfolio approach to investing. Let’s say a VC invests in 10 startups. Most of them will fail, or experience mediocre performance, in which case they’ll get merged or shut down. Maybe one in 10 will actually succeed. For that reason, each of the 10 companies must have the potential to be a home run—to sell for $100 million or more, or make the equivalent from an IPO (remember those?). Oh, and it’s got to happen in three to five years.

Also, each venture capital firm has a specific focus. They invest in companies in particular industries or locations, and focus on certain stages of development. Plus, VCs tend to make larger investments than angels – typically more than $3 million, though there are some exceptions.

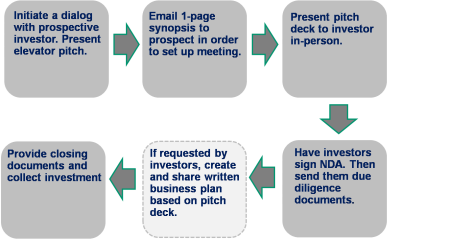

If you pass all those hurdles, be forewarned that raising VC can take a long time (plan on four to five months or more), and that their terms tend to be more aggressive than angel terms. Their pre-investment research or “due diligence” also tends to be much more thorough. Last but not least, you generally can’t just waltz into a VC firm—you almost always need a personal introduction.

Before approaching any angel, angel group or venture capital firm, do your homework. Know what they’ve invested in previously, and how those investments have performed. Know what types of investments they like to make now, which could be different from just a few months earlier. Know the backgrounds of the key players. And be sure you meet their investment criteria before you waste your time and theirs.

[1] Outside meaning beyond an entrepreneur’s capital, and that of his / her friends and family.

[2] A small number of VCs invest in seed stage ventures.

[3] http://wsbe.unh.edu/files/2007%20Media%20Release%20-%20Lori%20Wright.pdf

[4] Compared to angels, VCs place much bigger investments in far fewer ventures.

[5] One good way to find these groups is to visit www.AngelSoft.net

Posted by david ronick

Posted by david ronick